No, this isn’t an article about Jerry Garcia (who died in 1995) or Bob Weir (still very much alive).

As always, we find ourselves looking back on the past year, marveling sadly at the losses the music world has suffered. And as is my habit, I try to highlight some of the lesser known people who died, because the more famous have been lauded at length elsewhere. In fact, the first person I considered writing about, Maggie Roche, was the subject of an excellent piece in The New York Times Magazine, and I’m not going to try to compete with that—so read it at the link.

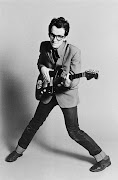

Instead, I decided to write about a few of the many guitarists that passed away in 2017, in many genres (and thanks to KKafa for writing so well about Larry Coryell, and Darius for writing about Walter Becker, so I don’t have to). There should probably be some sort of clever organizing principle, but I can’t think of one, so I’ll do it in order of the date they died:

Tommy Allsup: Rarely does a coin toss turn out to be a matter of life and death, but for Tommy Allsup, losing one to Ritchie Valens on a cold Iowa night in February, 1959 allowed him to escape the fate of Valens, Buddy Holly and The Big Bopper (and pilot Roger Peterson). But it would be wrong to focus only on Allsup’s luck—he was a fine musician, who was touring with Holly and went on to a long career as a musician, songwriter and producer. In addition to Holly, Allsup worked with Willie Nelson, Leon Russell, Bob Wills & His Texas Playboys, Asleep at the Wheel, George Jones, Don McLean, Marty Robbins, Johnny Cash, Waylon Jennings (also left off the plane in Iowa that night), Earl Scruggs, Jerry Lee Lewis, Dwight Yoakum, and the Everly Brothers, among others. Admittedly, despite that long resume, it appears that pretty much everything ever written about Allsup includes a reference to the coin toss. You can hear him tell the story here. And here he is telling more stories about Holly, before playing “It’s So Easy:”

Allan Holdsworth: Holdsworth is probably the best known of the guitarists in this article, and in some circles, he is considered to be one of the most influential guitarists of all time. I’ve referred to him before, most recently in a piece about a Gong song, one of the many bands that he contributed to over the years. Here’s what I wrote then:

If you don’t know who Allan Holdsworth was (he passed away earlier this year), find his music on the Internet. Days before his death, a 12 CD box set of his solo albums from 1982-2003, entitled The Man Who Changed Guitar Forever, was released. The title was taken from a proclamation on the cover of an issue of Guitar Player in 2008, and it isn’t an overstatement. That’s not to say that there aren’t other guitarists who changed the way guitar was played, but he’s certainly one of them. He was the favorite guitarist of Eddie van Halen; Tom Morello and Frank Zappa, among others, have cited him as an influence.

I really lack the vocabulary to explain why Holdsworth is also one of my favorite, if not my favorite, guitarist, so here’s a quote from Robben Ford, not a bad player in his own right: "I think Allan Holdsworth is the John Coltrane of the guitar. I don't think anyone can do as much with the guitar as Allan Holdsworth can." Apparently, he developed his style attempting to make the guitar sound more like a saxophone.

I may have first encountered Holdsworth from his Gong performances, or it might have been with his incredible playing in Bill Bruford’s band. And from there, I’ve listened to his solo work, his one great album with U.K., and his other recordings, with Tony Williams, Jean-Luc Ponty, Soft Machine and others. I saw him once, in the early 80s at the Bottom Line in NY, and it was a pretty incredible experience. Here he is playing with Bruford—the guitar solos kicks in at about 3:25, but don’t skip ahead—the band is too good:

Ray Phiri: Like Tommy Allsup, I suspect that most Americans, at least, are familiar with Ray Phiri for something that was really only a small part of his career. Phiri, a South African guitarist, singer, composer and arranger was featured on Paul Simon’s groundbreaking Graceland album, as well as its follow up, the more Brazilian-flavored Rhythm of The Saints. Ultimately, Phiri and Simon fell out over, as usual, issues relating to song credits and royalties. But in many ways, it was Phiri’s African/rock/blues fusion guitar, and his arrangements, that helped to turn Graceland into a huge hit for Simon. Nevertheless, Phiri’s career in South Africa, as the founder of The Cannibals and Stimela, and as an anti-apartheid activist is his most important legacy. That is why in 2011, the President of South Africa, Jacob Zuma, awarded Phiri the Order of Ikhamanga, a national honor, citing “the successful use of arts as an instrument of social transformation.”

Here’s Simon’s “Boy In The Bubble” from the 1991 concert in Central Park, which was later released as a live album. Phiri has a brief solo at about 2:55. Also visible on stage is Cameroonian guitarist Vincent Nguini, who played and recorded with Simon for 30 years, and who died in December, 2017:

John Abercrombie: There was a time, when I was in college, and for a few years afterwards, that I listened to a lot of jazz on the ECM label, which I got into initially by listening to Pat Metheny, with whom Abercrombie shares some sensibilities. In addition to his own, fluid, understated virtuosity, Abercrombie regularly played with other great musicians, including drummer Jack DeJohnette, bassist Dave Holland (who together comprised the Gateway Trio), bassist George Mraz, and drummer Peter Erskine, among many others. I sort of lost track of Abercrombie in the 1980s and am not all that familiar with his later work. But I still occasionally enjoy some of those early ECM albums. Here’s a live recording of the Gateway Trio, which highlights Abercrombie’s playing, as well as Holland and DeJohnette (who is one of my favorite drummers):

Phil Miller: I’ve written numerous times about bands and musicians from the Canterbury Scene, of which Phil Miller was a significant part. Miller, who was a member of Matching Mole, Hatfield And The North, National Health (which I wrote about here), and other bands, was a fluid and nimble player, whose soloing was imaginative and avoided cliché, but was also a skilled accompanist. I never had the chance to see any of Miller’s bands live, but have long enjoyed his recordings, particularly with National Health. And, based on this video, I wish that I had seen them (you can skip the first minute of noise, if you must):

Bonus Dead Bass Player--John Wetton: The bass is a type of guitar, right? And Wetton is probably more famous that anyone above, having had some actual hits, with Asia in the 80s. Wetton died just shy of two months after Greg Lake, another bass player with a similar voice, who Wetton ultimately succeeded in King Crimson (Lake, interestingly, briefly replaced Wetton in Asia, years later). In addition to playing in King Crimson, on three of their best albums, Larks' Tongues in Aspic, Starless and Bible Black, and Red, Wetton was a member of U.K., which originally included Holdsworth (and Bruford and Eddie Jobson), as well as Roxy Music, Uriah Heep, Wishbone Ash, and other bands, and collaborated with many musicians, including Phil Manzanera, Brian Eno, Bryan Ferry, Steve Hackett, and Geoff Downes. Here’s a link where you can download an unreleased track of Wetton playing with Robert Fripp and Phil Collins, and here’s a video of a live U.K. performance with the original lineup, synced to the album track: