Camel: The Flight of the Snow Goose

Anthony Phillips: The Geese and The Ghost

[

purchase The Snow Goose]

[

purchase The Geese and The Ghost]

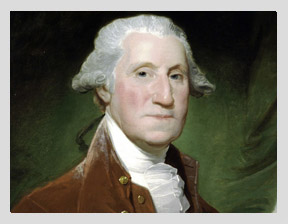

One of the joys of a theme-focused blog is that it gives you a challenge to wrack your brain and try to think of a related topic. And it can be fun to take the theme to an unexpected place. Clearly, the obvious way to interpret “Down” is consistent with the thumbnail being used to illustrate the theme—“toward or in a lower place or position.” But the word has other meanings, including certain feathers of a bird used for insulation, often from a goose. So, here we are.

Camel is one of those English prog-rock bands from the 70s that had some success, both critically and commercially, but aren’t generally grouped in the top tier of the genre’s acts. Nevertheless, they released a bunch of good albums and have continued to perform and record until the present day, with a dizzying revolving door of members surrounding founding member Andrew Latimer.

After releasing two albums with minimal success, the band decided to try a concept album. Rejecting a few novels to base their work on, they ultimately decided to attempt to create a work based on a 1941 novella by Paul Gallico (a prolific writer probably best known for

The Poseidon Adventure), titled

The Snow Goose. It tells the very sentimental story of the friendship and love between Philip Rhayader, a disabled artist living in a remote lighthouse in Essex, England, and a local girl, Fritha. A wounded snow goose is nursed back to flight by Fritha, whose friendship with Rhayader grows, while the goose returns over the years to the lighthouse. Rhayader uses his sailboat to rescue hundreds of soldiers in the Dunkirk evacuation, but is lost. The goose finds Fritha on the marshes, which she interprets as Rhayader’s soul leaving her, and she realizes her love for the lost man. The lighthouse is leveled by German aircraft, destroying all of Rhayader’s work, except for a portrait of Fritha, as a child, holding the injured snow goose.

The story struck a chord, and the book won an O. Henry Prize in 1941. It was read on the radio in 1944, turned into a BBC TV movie in 1971 featuring Richard Harris (as the goose—just kidding), and that won a Golden Globe and was nominated for both a BAFTA and Emmy.

When Camel announced that it planned to release their musical adaptation of the book, Gallico gallantly threatened to sue the band (yay, lawyers!), so they were forced to call the album

Music Inspired By The Snow Goose, and they had to abandon the idea of using lyrics based on the text, rendering the album fully instrumental. Despite these obstacles, the album, released in 1975, was both a critical and commercial success.

It is a beautiful, moving work, featuring rock instrumentation along with the London Symphony Orchestra (and, on one song, a duffle coat, used to simulate the flapping of wings).

It is hard to pick a favorite song, but to be theme-appropriate, I picked “Flight of the Snow Goose,” which starts off slowly, but builds to a triumphant end.

In doing my research for this, I found a review which claimed that the Gallico novella also inspired another song, Anthony Phillips’ “The Geese and The Ghost.” Turns out, that

isn't true. In fact, the title

derives from two sounds on the ARP Pro-Soloist synthesizer which was used on the album.

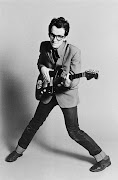

Phillips was the original guitarist in Genesis, but left after recording their second album,

Trespass, ultimately being replaced by Steve Hackett. Phillips left due to a combination of stage fright and other health reasons, and an aversion to being in the public eye. After leaving Genesis, Phillips decided to study music, and didn’t record anything for a number of years.

His solo debut,

The Geese and The Ghost, featuring some music that he had worked on while still in Genesis with friend and former schoolmate Mike Rutherford, and solo compositions, was released in 1977. In addition to Rutherford, Phil Collins provided some vocals (recorded before he succeeded Peter Gabriel as Genesis’ singer) and Hackett’s brother John added flute.

In general, the album is somewhat folky, with orchestral flourishes, and the title track is beautiful. Genesis fans could definitely hear a kinship to some of the quieter moments of

Trespass.

Phillips went on to release music to little commercial success, more successfully create “library music” for use in films and TV shows, and appear on other artists' albums playing guitar and keyboards.

In fact, in 1982, Phillips appeared on Camel’s album

The Single Factor, and co-wrote a song with Andy Latimer. That album is utterly devoid of any goose-related material (which unfortunately cannot be said of our local athletic fields).