Friday, April 8, 2016

History/Again: Gil Scott Heron

Posted by KKafa at 12:16 PM View Comments

Labels: Gill Scott Heron, History

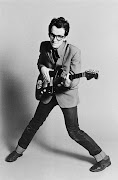

HISTORY/AGAIN : Mark Knopfler

Some artists clearly love a true story, if only and at least as a template from where to launch into fanciful forays of imagination. Knopfler is someone who seems forever digging around in the past as inspiration, uncertain whether he likes to research or has just a vast accumulated knowledge. Probably a bit of both, having trained and worked as a journalist, before a degree in english and working as a college lecturer, his career in music on a slow side simmer until the relatively advanced age of 28. Of course, Dire Straits became huge and possibly so ubiquitous that they and he became an easy target for the taste police, deeming him dull and anachronistic bombast, an irony given the majority of their/his songs retained a virtue of their lack thereof. I like him and always did, an early adopter, as Sultans of Swing soundtracked my student years in London. (Come to think of it, it's now so long ago it probably counts as history in its own right!) While Dire Straits dabbled in ye olde historical, meaning more WW1 than Italian familial vendetta, it is in his less acknowledged and still smouldering solo career that this side of his songwriting style has really found wings, now 9 albums strong, along with collaborations with, amongst others, Emmylou Harris and Chet Atkins.

Does the legend of Imelda Marcos' shoe cupboard count as history? I think it does, even if the song is a retread of that song indirectly referred to above. Arguably one of the weaker cuts from his first post Straits non soundtrack output, it wasn't until his 2nd record that he really found his narrative skills. The title track from that record follows, and I like to feel it alerted many a listener to the hitherto untapped world of cartography. A beautiful duet with James Taylor, himself no stranger to a shot at history*, it remains the high point of live performance.

Whilst his next record was largely a paean to his Northumbrian roots, it was 2004's Shangri-La that really outed his love of the biographic, with songs inspired by Elvis, by Sonny Liston and the UK King of Skiffle, Lonnie Donegan. And this one, about the developer of McDonalds, yes the meat patty people, Ray Krocs, with many of the lyrics, included below, lifted directly from his autobiography.

A distinct feature of successive output has been the greater immersion in traditional and rootsy forms, whether an anglo-celtic folk tradition or from country music. Lyrics increasingly based upon folklore perhaps, than hard evidence, but no less cinematic, like this whimsy around the Reivers, cross-border bandits really, who flitted between the english north and scottish south, sheep stealing, cattle rustling and generally causing havoc. (Hence the derivation of the word bereaved, meaning the fate of those who had been "reived".)

His next work substituted border cowboys for pirates, again using the metaphor of a band of marauding rogues for, maybe, the lifestyle of an itinerant rock and roll band. By this stage I fear the lyrical conceits get the better of his tune smithery, but it continued to add to his reputation as a reliable and authentic musician, selling respectably.

Finally we come up to date with last years 'Tracker', more confirmation of his comfort zone, but again featuring songs relating to real-life individuals, one to little known poet, Basil Bunting, and another musing on the legacy of novelist Beryl Bainbridge and her attempts at the Booker prize, the prestigious UK grail for novelists, and in style a tip of the hat to earlier musical memes.

So this is but a mere dip into the historical sources put to use by this gifted and self-effacing Northumbrian, clearly a well-read man, usually issuing these songs as either the title track or lead single. In concert he can seem embarrassed by his earlier successes, oft dashing off his hits with a grimace before another earnest folk-hued story unfolds. I suspect the audiences still come mainly for those hits, but overall, given the choice, I think I prefer the best of his solo work.

(*Machine Gun Kelly was written by Taylor guitar to go, Danny Kortchmar.)

Start buying!!

Posted by Seuras Og at 8:20 AM View Comments

Labels: dire straits, History/Again, James Taylor, Mark Knopfler

Monday, April 4, 2016

History/Again: Kingston Trio

[purchase Here We Go]

An article in an old (not so old that it is history yet) NewYorker I recently read an article that indicates that I wasn't off the mark in pegging the Kingston Trio as one of the seminal forces that brought rock to the world ( but that is history). Among the piece's other observations, the article posits that - along with the 45RPM, the 33 1/3RPM and transistors radios, it was record players cheap enough that kids could have their own and be freed from the constraints of listening to music in the presence of -and on the hi-fi stereos of- their parents that helped bring about the rock explosion.

The songs of the The Kingston Trio's 1960 album (Here We Go Again) in which the concerns of the world appeared to be "eating Goober peas", "hauling away" at the oars of a boat on a stormy sea, or yodeling as you climb the Matterhorn, make their world appear rather light and removed from our current state of affairs. Much like Simon and Garfunkel, or Bob Dylan - they were among those that bridged folk and pop and lead to a "beat-ier" kind of music that lead to the Beat-les. Rock music didn't become mainstream until the Kingston trio and Simon & Garfunkel & Bob Dylan (and the Beatles) cut a path from folk music to rock music.

The NewYorker article mentions that teens getting their own recordplayers partially liberated them from parental oversight, but - for me - it was my parents who brought home the Kingston Trio's 1959 album "Here We Go Again". We listened again and again and now the Kingston Trio is relegated to ... history. My siblings and I memorized the entire album and can still recite the whole thing word for word more than 50 years later. If my folks had known that it was going to lead to the psychedelic music of the 60s that we soon were enjoying, I wonder if they wouldn't have left the album on the store shelves.

More history from Here We Go Again: (As if the Civil War itself isn't history enough in itself)

Posted by KKafa at 12:26 PM View Comments

Labels: Again, History, The Kingston Trio